Thursday, April 29, 2010

Visceral Bodies at the Vancouver Art Gallery by John Luna

The Vancouver Art Gallery

Part of the Cultural Olympiad, the exhibition Visceral Bodies at the Vancouver Art Gallery (curated by Chief Curator/ VAG Associate Director Daina Augaitis) is presented in dialogue with the accompanying show of Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical studies, The Mechanics of Man. Visceral Bodies is itself divided into three sections, “Visceral Bodies”, “The Scientific Body” and “The Fragmented Body”, invoking both hard and social sciences, or as Gallery director Kathleen Bartels put it, “the body as a subject of anatomical, social and psychological study.” Strange bedfellows with skytrain station advertisements displaying the sleekly x-rayed physiques of athletes in motion (faster without their skin on), the notion of the paired exhibitions is to present Leonardo’s sketches -taboo-transgressing scientific humanism - alongside a more radical inquiry in which ‘humanism’ as such may not survive the procedure by which the taboo is excised.

At the entrance to the gallery containing “The Fragmented Body” is a collage by Kenyan-born, New-York based artist Wangetchi Mutu, I belong to you, you belong to me (2007.) Gracefully negotiating attraction and repulsion, smooth skin cut from advertising and illustration presents a soulfully luxurious tension that is ruptured by clutches of plastic pearls that spall incomprehensibly, uncomprehendingly out of unexpected orifices. Skin as such (and our gaze skimming it, drawing pleasure) becomes inadequate to cover what lies beneath (an interior decomposition, or more threateningly, like an expanding universe or spawn of maggots, recomposition.)

Mutu’s materials are at one with her content: Mylar (the synthetic cousin of vellum, calfskin) feels like skin and is manufactured for drafting; craft store ‘pearls’ are at once both agitating grains and corrosive kitsch. Everything frightening in its natural manifestation has its synthetic echo and all of it cajoles, upsets, and ultimately objectifies our involvement. It seems too obvious to say that Mutu’s imagery speaks to gender or race (in another gallery, we see more collages made from old medical illustrations of sexual organs infected with disease), or rather of one race or gender’s view of another exclusively. They are the fear of multiplicitous categories, of mutation, loss of resolution’s dignity and segregating language. They are powerful because they acknowledge that desire undoes these things as readily as disgust or dread.

Other works in this gallery are not as strong. Shelagh Keeley’s Writing on the Body (1988), is a massive multi-panel wall piece consisting of drawing as deliberately crude atavistic/confessional sign systems referencing bodily fluid, internal organs and amputated /alienated body parts. It was originally a site specific piece, in which the artist covered the walls of a gallery in Tokyo with a mixture of wax, Vaseline, and pigment. Here the panels have been cut out of their original architectural environment and propped against the wall, matter-of-fact slabs mostly absent of tension. The space the bodies would seek to assemble themselves in cannot thicken around them or attenuate threateningly…it has become a matter-of-fact slab.

This point is underscored by a small row of drawings on vellum by Betty Goodwin on the opposite wall. The Goodwins are taut by comparison; merciless in their ability to marshal stray swipes of carbon into a deft, dramatic economy. Positioning these two bodies of work across the gallery from one another robs each of something important. Keeley’s work looks like poorly informed illustration when it means after all to appeal directly rather than portray; the terse mythopoeia of Goodwin’s drawings get crowded out by a much larger work that seems to extrovert and vulgarize its palette and technique. It’s a superficial comparison.

Overall, it has to be said, that the gallery would benefit greatly from some judicious editing. The overwhelmingly sensuous affect of works as varied as a papier-mâché skin by Kiki Smith and a video of several sonorous larynxes by VALIE EXPORT would have more impact in an evacuated, clinical environment, the lucid surveillance of a contemporary art space merging with the sterile caution of the care facility.

Perhaps the only work that makes a virtue of the crowding is a haunting sound piece by Teresa Margolles called Sonido de la Morgue/Sounds of the Morgue (2003). A pair of heavily insulated headphones hanging from the ceiling in a corner proffers listeners the sound of an autopsy being conducted on an anonymous murder victim in Guadalajara, Mexico.

The sounds are mostly a continuous, slushy slicing and sawing remarkable for both its professional efficiency and its homogeneity. I am reminded immediately of the seemingly endless string of unsolved murders in Sonora County, excoriatingly documented in Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2666, and like that narrative, the relentlessness of the situation is by turns both horrifying and giddily absurd.

In a crowded space the sound becomes gravely intimate, the grim reaper sharpening his scythe heard as cricket legs rasping together on the fringe of your hearing. It almost feels consoling to note its persistence as one strives to shut out other sounds, feeling the relief that the worst is after all over and the procedure carries on unhurried. It’s only when one tries to have an interior monologue in response, that the continuity of the sound becomes gratingly intrusive. Death is also becoming distracted.

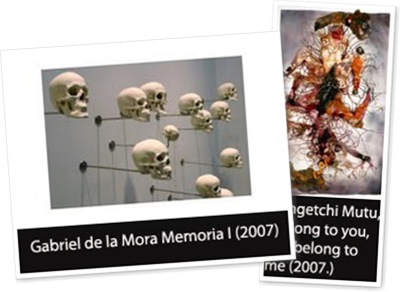

The next section, “The Scientific Body”, suffers from overcrowding, but in a way that more directly undermines the operation of some of the artworks. Notably, works by Gabriel de la Mora and Mona Hatoum propose the artist as manipulator of medical imaging, and rely on a place for the viewer’s body to relate directly to this imagery so as to be implicated in its projected diagnostics.

Mona Hatoum's Deep Throat (1996) presents a blandly innocent dining table and chairs, with a screen neatly inserted on the bottom of a dinner plate. The screen shows a video of an endoscopic exploration of the artist’s digestive tract. The title of this work calls up the famed pornographic film of the same name, with its overlapping associations of eating, speech, and sexual penetration. The arrangement also suggests an homage to the work of surrealist René Magritte, notably Portrait, 1935 (a slice of ham on a plate that stares out at the viewer from an unblinking eye) and The Rape, 1934 (a face whose naïve features are a woman’s nude torso.) The implication is of sexuality without intimacy, but more properly of a body alienated from itself. Like the victim of an eating disorder or childhood abuse, the self of Deep Throat has lost the horizon upon which to envision the negotiation of its thresholds. Paradoxically (and pathologically), nothing can be controlled but everything shall be witnessed.

The problem with the presentation of Deep Throat here is that the room is too crowded to approach the table at some remove, as ordinary domestic tableaux. As a result, the initial sting of bourgeois betrayal is lost. Likewise, the chair is barred from sitting with both conspicuous plastic strapping and a large sign. This seems like museum security overkill, and disrupts the fantasy that it is the viewer’s body that is invited to sit and stare, and by extension, weakens the implication that the abyss we gaze into represents our own internal workings as much as the artist’s.

Likewise, Mexican artist Gabriel de la Mora’s Memoria I (2007) wants to make a space for the viewer as participant. Using MRI technology and a 3D printer, the artist produced seventeen replica skulls based on those of his close family from both live and posthumous scans. These include the skulls of a stillborn sister and deceased father, all placed at their owner’s respective height with the exception of the tiny infant, who appears as if cradled at chest level. As a memento mori or vanitas (reminder of death’s inevitability), the piece is compellingly direct, yet also delicately tactful. At a distance, the synthetic skulls emerge only gradually from the background wall, calling forth their idiosyncrasies and differences as they do so. Up close their appeal becomes more immediate and irresistible, their evident fabrication hinting at both material and virtual presences; the now and the elsewhere, and the later all at once. In a tight space, this transformation is not enabled, and the pieces can too readily be taken up as anthropological curiosity (more Mexican Day of the Dead fun), their mirroring potential passed over.

In the end, it is not really only a question of curtailing or choreographing certain works to a greater or lesser degree. The more important issue is how the various works come together, and it is here the charge of crowding becomes most detrimental. Having two works each by Wim Delvoye and Marc Quinn, for example, means that each piece by a given artist, though distinct formally and conceptually, has more obvious similarities with its sibling than with other pieces in the exhibition, so that the artist’s brand is more strongly enforced than thematic links from work to work across disparate disciplines and milieu. Of two sculptures made by Berlinde de Bruyckere, one maintains a delicate balance of sacred and profane grotesquerie while another is less subtle, weaker in placement and ultimately distracting.

In some cases, artists should have been reconsidered, relocated or not included at all. David Altmejd’s work feels generally ill-placed and out of context. Antony Gormley’s Drift II (2009) accomplishes itself brilliantly in a room of its own while Luanne Martineau’s provocative Dangler (2008), stuffed into a corner by a doorway, is hard put live up to its name. Martineau’s work is strong but much subtler in reality than in reproduction. To deny the work its softer operations is, significantly, to curtail the viewer’s body as well.

Visceral Bodies suffers from organizational problems that obscure both the power of individual artworks and the greater gesture of curatorial intent. I hope it does not sound like post-Olympic grousing to state that the challenge faced by the proposition of Visceral Bodies are a problem of curating as commuting meaning versus programming as engendering spectacle. The body is a potent frame of reference when come upon unexpectedly, offering both the informational shock of the facts of life and the contemplative unpeeling of their artefactual presence. To repeat this revelatory act of skinning the cat so many ways in such close quarters however, is to risk robbing mimesis and allusion of their power to transform in any lasting way, which is to say, within the body of the viewer’s sensibility. Denied sensibility, the works must become bodies without politics.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment